Results 451 to 480 of 1494

-

2013-06-27, 10:56 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I own a copy. My buddy Matt Easton wrote the introduction ;) It's a great book of anecdotes.

They weren't obsolete, read up a bit on the Russian front in WW I. They just has a much more limited (increasingly limited) role.Lancers with lances and swords were pretty obsolete by 1898.

Emphasis on the 'if' and the 'some'. Read up on it a bit further, including in the book you are citing. Quite often the swords were so bad the pommel was preferred for use as a knuckleduster than the actual blade itself.As far sword quality goes, accounts differs. If properly sharpened, some regulation British swords did good service.

This was an intentional design feature of many swords, see Petter Johnsson...(snip)One blade from the Mary Rose, while possessing a hard edge, was soft iron with a very thin outer layer of steel that would not survive many sharpenings.

Yes but the plural of anecdote is not statistic, and that doesn't change the reality - swords from the mid 16th century on back to the early Medieval period were usually hand-made by experts, master cutlers and sword smiths. European military swords in the 17th, - 20th century were usually mass produced using very shoddy methods, often not even properly sharpened, and / or kept in metal sheathes which dulled the blades and so forth, and English swords in particular were notoriously bad, worse than continental designs, according to the English themselves.One Viking-era sword was miserably soft and would not have held a decent edge. See The Sword and the Crucible by Alan Williams for details.

G

-

2013-06-27, 12:02 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2010

- Location

- Albuquerque, New Mexico

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

They only meaningful advantage the sword has over the pistol is that it doesn't require ammunition. Even today swords are theoretically useful in war - people still get killed with knives and improvised close-combat weapons on occasion. They're still obsolete.

I've read the whole thing and various other nineteenth-century sources. Sometimes regulation swords performed as bludgeons, other times in caring hands they cut as well as one could expect. While opposing blades tended to cut better, the better British sword lines did fine as long as somebody took the time to sharpen them.Emphasis on the 'if' and the 'some'. Read up on it a bit further, including in the book you are citing. Quite often the swords were so bad the pommel was preferred for use as a knuckleduster than the actual blade itself.

No, there's no benefit from having such a thin layer of hard steel on the outside of the blade. Alan Williams explicitly describes the design as lacking. Moreover, Williams disputes the notion that an iron core provided any benefit, as steel in period was tougher (wholly or in part because of lower slag content, if I recall correctly).This was an intentional design feature of many swords, see Petter Johnsson...

Data in The Sword and the Crucible don't really support this notion. The metallurgical quality of European swords apparently quite erratic before the fourteenth century, and in the Renaissance era many/most were still of dubious quality. Indicating his low opinion of the quality of early European swords, Williams writes that "[e]even in the 16th century many ordinary soldiers carried blades little better than those of a thousand years before." The numbers in The Sword and the Crucible only go into the seventeenth century for Euorpean swords, but those indicate that blade quality in terms of hardness on the whole improved up to that point. However, I can't find any metallurgical tests of nineteenth-century British swords, so I guess it's possible that they could be even worse than the medieval average. Given the overall improvement in steel production and their performance when properly sharpened, I doubt that. I imagine it depends on the exact pattern in question and all that. Williams describes a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Indian sword as one of the best swords made anywhere, anytime because of its metallurgical properties, so it's not terribly surprising that Indian swords typically outperformed poorly sharpened British regulation blades.Yes but the plural of anecdote is not statistic, and that doesn't change the reality - swords from the mid 16th century on back to the early Medieval period were usually hand-made by experts, master cutlers and sword smiths. European military swords in the 17th, - 20th century were usually mass produced using very shoddy methods, often not even properly sharpened, and / or kept in metal sheathes which dulled the blades and so forth, and English swords in particular were notoriously bad, worse than continental designs, according to the English themselves.Last edited by Incanur; 2013-06-27 at 12:07 PM.

Out of doubt, out of dark to the day's rising

I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope's end I rode and to heart's breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin and a red nightfall!

-

2013-06-27, 01:10 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

This fits with what I've read. During the industrial age swords were usually made from better quality steel -- primarily because it was easier to mass produce better quality steel. I think in the renaissance they *could* make high quality blades, but the common soldier wasn't going to have one, and the majority of swords were probably of low quality.

-

2013-06-27, 02:06 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I recommend to both of you read Peter Johnsson on the subject of the ferrous composition (and design) of medieval swords.

As to the difference between 19th century and say, 16th century swords, just talk to some collectors. Have you handled any?

In a nutshell, the problem with 17th-19th century swords wasn't just lack of sharpening, and there is much more to a swords design than the quality of the steel. It's a matter of weight, balance, harmonics, temper, ability to hold an edge, flexibility and so on. They made many things very well out of steel in the 19th Century, bridges, towers, railroads, boilers, cannons, rifles, but swords? Not so much.

Indian swords up to the 18th are the exception because some of them are of wootz steel, using a crucible steel making technique that was lost by the 19th (though supposedly rediscovered now).

Alan Williams is a recognized expert on armor, on swords, he's a bit more... controversial to say the least.

What is a 'common soldier' in the late Medieval / Early Renaissance context, exactly? That is a far more easily defined entity in the 18th Century than the 15th I think... ;)

G

-

2013-06-27, 03:14 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2007

- Location

- Tail of the Bellcurve

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Last edited by warty goblin; 2013-06-27 at 05:40 PM.

Blood-red were his spurs i' the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet coat,

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway,And he lay in his blood on the highway, with the bunch of lace at his throat.

Alfred Noyes, The Highwayman, 1906.

-

2013-06-27, 07:21 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Galloglaich -- can you give us a hint as to what Peter Johnsson has to say on the subject of the variations in quality of steel and sword design during the Middle Ages, and comparatively to later periods? [I've only had a chance to glance at the titles of the videos, but I'm hoping to find time to watch the last one, that one looks really cool]

As for sword design -- I have handled some old swords, although it's been a while since I've handled anything as old as 16th century. Recently I got to handle a M1840 Dragoon sword, and I was impressed with the weight and balance (especially for a sword nick-named the "old wrist-breaker", or is that the M1833?) -- but I had been carrying around a modern replica saber that weekend. ;-) I'm similarly impressed by the weight and the amount of spring in my original Vetterli bayonet.

I would imagine, that anybody who repaired a cracked sword with solder would be considered a "common soldier", but I suppose I could be wrong on that. ;-) (Of couse defining common soldier is going to depend upon when and where, and what we mean when we say "common").Last edited by fusilier; 2013-06-27 at 07:22 PM.

-

2013-06-27, 09:23 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Well, I'm neither a swordsmith nor an engineer, and I can't claim to fully grasp Peter Johnsson's theories, nor am I really qualified to summarize his work, but I'll try a simple analogy.

Most people today grok that Japanese swords are partly made with a low-carbon or iron spine forge welded to the much harder steel blade, as an intentional feature of the design. Many experts who have done destructive testing (like Alan Williams) noted to their surprise that a lot of very fine quality medieval swords have something like wrought iron in the core even when they have very high carbon steel edges with an excellent heat-treatment. Peter seems to be saying that there is a similar design philosophy at work. At any rate, he states categorically that putting iron in is an intentional part of the blades design.

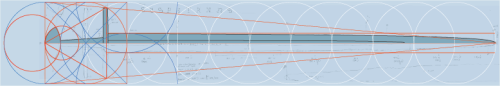

He also made an analogy of his own which I thought was very thought provoking. Noting the cliche that many have repeated, that medieval swords were like 'sharpened crowbars', he suggested that their actual structure is more like an airplane wing.

He goes on to point out the harmonics of medieval swords, how they all have a sweet spot where there is very low vibration right at the point you would normally cut with on the blade. If you have done any test-cutting you know how critical this is if you want the sword to actually cut well, let alone fence with it. He suggests that this effect is achieved by using the same kind of geometry in the design that was used to build cathedrals, drawn out with circles and squares and based on a sort of numerology that educated people in this period were obsessed with. All this was imbued with Christian symbolism but linked with older syncretic traditions.

He gets into a little summary of all that in this article, here:

http://www.peterjohnsson.com/higher-...per-reckoning/

He also notes that swords were made not by some sweaty, half naked blacksmith pounding away in the village square, but by groups of highly trained specialists: The cutler or messerschmidt made the design, and subcontracted out to the ironmonger who made the steel, the smith who made the sword blank, the hilt maker who put it all together, the sword polisher who sharpened it, and so on, again a lot like they do with traditional swords in Japan. (Johnsson does not make the specific analogy to Japan, that part is me)

For more on this theories you can read this book, it has a pretty long essay about all this stuff by mr. Johnsson in there.

http://www.amazon.com/THE-NOBLE-ART-.../dp/0900785438

I have handled a few antique swords, quite a few 'sword like objects' and some very high end replicas. I own a few 19th Century sabers myself and I love them, the ones I have are probably low- to middle-end in terms of what was available 150 years ago and they are vastly better than any replica I could afford; but they simply don't compare in terms of overall feel, subtlety, grace... scariness, to the (very few) medieval blades I've had the privilege to handle.

G

-

2013-06-27, 09:45 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2007

- Location

- Tail of the Bellcurve

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Perhaps this is common knowledge, but I was particularly struck by his discussion of how little the center of mass mattered to the handling of the blade. Instead he focused on the points the blade tends to rotate about when force is applied to the hilt. This was the first time I had ever heard anything like this rigorously considered when talking about blade dynamics.

Blood-red were his spurs i' the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet coat,

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway,And he lay in his blood on the highway, with the bunch of lace at his throat.

Alfred Noyes, The Highwayman, 1906.

-

2013-06-27, 09:57 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2010

- Location

- Albuquerque, New Mexico

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Williams is perhaps too dismissive of the Mary Rose sword, as its edge is quite hard (about 500 VPH) and presumably could cut well until the layer of steel wore away. On the other hand, that one Viking sword -the worst of all the blades analyzed by Williams - had an edge hardness of 101 VPH, which is barely more than pure iron. It could only have been a miserable cutter, though perhaps a decent bludgeon.

The problem with supposing medieval and Renaissance-era smiths intentionally used soft iron cores to make blades more resilient is that, according to Williams, in Europe during this period iron contained more slag than steel and thus was more brittle.

As far as nineteenth-century swords go, I've never handled originals from any era, but I'm skeptical that they were significantly worse than medieval swords as a rule based both on metallurgy and period accounts. According to numerous sources, sharpened and skillfully wielded British blades cut as well as you could possibly expect: skulls cloven, arms removed at the shoulder, legs hacked off, and so on. For example, the account of Nizam's irregular cavalry using refitted dragoon blades to great effect indicates at least some mass-produced British steel was hard enough to hold a keen edge. Accounts of British swords breaking or bending certainly exist, but on the whole - depending on the exact model in question - the metal seems decent. Countless cavalry authors stressed sharpness, and there's little question that British swords were sometimes if not often too blunt because of steels scabbards and lack of sharpening.

With regards to the obselesence of the sword and lance in 1898, I recommend George Taylor Denison's argument from 1868. Denison ends up recommending retaining the lance and saber primarily for the pursuit and the intimidation factor - not useless arms, but not really for fighting as they were before.Last edited by Incanur; 2013-06-27 at 10:01 PM.

Out of doubt, out of dark to the day's rising

I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope's end I rode and to heart's breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin and a red nightfall!

-

2013-06-27, 11:59 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Thanks Galloglaich -- I did manage to start one of the lectures and noticed how he mentioned certain things like "root 2" -- I've actually studied the history of mathematics a little bit (briefly formally), and so I'm perhaps not so surprised by how medieval swords were designed. He seems to be applying Euclidian geometry to the layout of swords, and honestly I'm surprised that no one else attempted that; seeing as mathematics was dominated by geometry at the time, specifically the kind of "constructible" geometry that Euclid describes. I suppose the general thought had been that people simply modified existing designs and therefore swords "evolved" naturally overtime, so why bother looking for some evidence of building to general principles? (however, it could be that swords did evolve to a point where the good ones, just happened to follow certain geometric rules). I do need to watch the full lecture though, it looks like cool stuff.

I think Incanur still has a point -- the material question aside, the use of swords had changed, and it's understandable that it's form would have changed too. On the other hand, with increased standardization, if the board of ordnance adopted a . . . let's say: "suboptimal" . . . design, then you would have a bunch made to that pattern, and troops grumbling until something better was adopted (or using something unofficial). Unlike in the middle ages, where if a swordsmith produced a poor weapon it probably went back into the pot; at the very least there probably weren't a few thousand of them made.Last edited by fusilier; 2013-06-28 at 12:12 AM.

-

2013-06-28, 04:26 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I just finished watching the last video, linked from the . . . link . . . anyway --

If you're interested in how medieval swords were designed, you should watch this. It's very good. I do have some complaints: I think he might be reading too much into some of the more mystical aspects of numbers and geometry (not that they didn't exist -- they had well before the middle ages -- just that you can read them into anything), likewise his talking about irrational numbers and rational numbers in geometry misses the mark a bit (the power, and popularity, of geometry is that it side-stepped those "issues"). Also, he refers to music as mathematics applied to time, which is fine, in the medieval period the study of music was basically a branch of mathematics, but another way of thinking about music is "ratio theory", which was very important during the period.

I think what it boils down to is quite simple: the geometrical processes he describes, are Euclid's geometry --> those were the drafting tools available to Europeans at the time (i.e. the straight edge and compass). Johnsson shows, quite convincingly, how those tools could be used to design a sword.

Very enjoyable to watch.

-

2013-06-28, 10:29 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

On Peter Johnsson's theories, it's true that whether the correlation to the 'sacred geometry' accidental convergence of utilitarian design vs. the intentional application of the patterns of Euclid is impossible to verify yet, but he has had the opportunity to evaluate a lot more swords than anyone else I know of, both as a professor and in the capacity of his job as a designer for Albion, and he has noted that this pattern with the squares and the circles and the harmonic 'sweet spot*' on the blade exists in almost every sword he's examined from around the 12th century through the 16th, but not in Viking swords or swords from the 17th century or later (at least as far as I'm aware).

Which makes sense because this whole design philosophy, and the numerology / astrology / theology that goes with them is a specific type of syncretic mixture of Greek, Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Roman and probably several other cultural motifs, was a pretty characteristic cultural theme in the Medieval period, which declined in influence in later years for various reasons.

On the sacred geometry, it's also valuable to look at the efficacy of the designs of the medieval Cathedrals. Look at something like the Strasbourg Cathedral, made in the 15th century, it's essentially a skyscraper, over 460 feet tall, taller than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Made with no rebar, with no steel girders, just cut stone and glass... and air. And it's lasted more than 500 years of weather, wars and wear. I don't think many buildings on that scale today will last so long Though described by some as 'architects', the builders and designers were actually just craftsmen, master masons. They were using the same kind of geometry Peter Johnsson describes.

By contrast, the "Flatiron Building" in New York, built in 1884, one of the tallest skyscrapers of the 19th Century, (actually 20th, it was finished in 1902) at 285 feet tall:

Also a beautiful building, with an impressive design, but not made with the same level of craftsmanship, I would argue.

As for all the wonderful tales in Swords of the British Empire (which I do highly recommend as it's full of excellent material for gamers or anyone interested in history, war, or fighting) of people hacking heads in twain and so forth, this no doubt did actually happen, but it's also true that in just as many anecdotes you hear about how the blades performed poorly. A few years back, 800 thousand people were hacked to pieces in Rwanda using machete's and gardening hoe's with blades stamped out of sheet metal and barely sharpened, it's still possible to do extremely grievous bodily harm with such crude weapons. I'm just saying that, anecdotally, it seems that the type of catastrophic wounds like severed arms and so on, were more common in a medieval context, which is I think both because the swords were a lot better made and because the people using them were much more skilled in their use than conscripts in the English army in 1890. In later periods it seems to me that it was much more often the case that cuts were superficial, couldn't cut through clothing and so forth.

Like I said I do have some stats on this from remission letters which I'll post soon, though I can't honestly say these really prove anything they do support what I'm suggesting, and they are interesting.

Regarding the reasons for the difference, as Fusilier noted, bad designs could be reproduced in the tens of thousands in the 18th or 19th century, (and across decades of time as well) since sword designs were decided by committee's in the military hierarchy and the common soldier had little choice of what to use, but in addition to that, the production methods for swords were also very different, and IMO, inferior.

But ultimately all this is just opinion, it's too complex of a dataset to really be able to speak of definitively, at least yet. We are all looking at basically the same sources, we can draw our conclusions as best we can, beyond that, nobody has a monopoly on the truth. One thing I've learned doing research these last 12 years, is that "all interpretations are provisional" (and that is an understatement.) All I can really give is my opinion, and the best information I can find at this moment, (which will probably change in a few weeks!)

G

*I think this may be one of the hidden elements which contributed to the superlative cutting performance many have noticed with some of his Albion designs which were very closely derived from antiques - like the famous 'Brescia Spadona'.

-

2013-06-28, 01:03 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2010

- Location

- Albuquerque, New Mexico

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I'm skeptical of generalizations about medieval vs. nineteenth-century sword performance there's so much variation in each. From what I remember of fourteenth-century English coroner's rolls, the few sword attacks recorded in the this civilian context resulted in no severed limbs or anything like that. Instead, these sword blows inflicted dangerous but modest wounds and didn't tend to immediately incapacitate with a single stroke. In one case a man struck on the head by a sword initially fell but got right back up, fled, and in the end killed his pursuing attacker with a blow to the head from a knife. (See page 90.) The folks in the fights aren't necessarily warriors, but it's one example of how medieval European swords didn't always produce spectacular wounds. Knife and dagger thrusts - far more common here - seem more deadly and more likely to incapacitate from this limited data set, but we know from other sources that good swords in skilled, strong hands deal out devastating injuries.

Honestly I can't think to too many specific examples of severed limbs or heads from medieval and Renaissance times, though the sixteenth-century coroner's rolls I link to earlier contain various deeply penetrating and immediately incapacitating cuts to the head.Out of doubt, out of dark to the day's rising

I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope's end I rode and to heart's breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin and a red nightfall!

-

2013-06-30, 03:14 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Well we do have some evidence to go on. I don't think anything can be proven by any means, and you are right saying that generalizations are dangerous, but I have reasons for my opinion. And of course, claiming that swords in the 18th century were better than or equivalent to Medieval swords is also a generalization and an opinion.

We really can't know definitively, but we can make an educated guess.

We have literary evidence. From the Norse sagas and edda's to Medieval novels like Tiran lo Blanc, which refer to severed limbs and decapitations and so forth, (I would even venture to say that most fights in the Norse sagas depict serious wounds to someone's limb, they even named their swords things like 'foot-biter' and so on) though they also refer to other things which seem implausible so we have to take such tales with a grain of salt.

We have forensics. Famous battles like Wisby, Towton, Kutna Hora which have been partly excavated and subject to some forensic analysis. We do see a fair number of severed limbs, I know there were quite a few at both Wisby and Kutna Hora in particular. I've posted images like this one (from Wisby) to this thread before:

.jpg)

Then we have the fencing manuals. We see a lot of images like this one from Talhoffer

And as you have already shown, we do have a lot of documentation from things like court records and so on. Earlier this year, I was lucky enough to get a small paper on urban militias into a peer reviewed journal linked to the HEMA community, published out of Hungary, and released at the fencing tournament in Dijon, France back in May. When I finally got my copy last week I was able to read the other articles in the journal, one of which deals with this very subject.

The author (Pierre-Henry Bas) examined hundreds of medieval remission letters from France and Burgundy. These remission letters are sort of like pardons from the King of France or the Duke of Burgundy, which were necessary to avoid punishment in the event of getting into a fight in which someone was killed or seriously injured.

This was not the same system in England (from whence we have the coroners rolls) or Germany. England was much more strict, it was common for people to be hung for dueling or fighting with weapons if anyone was killed or seriously injured, (or even if nobody was); in Germany (in most of Slavic and German speaking Central Europe) it was the opposite - you could get away with it so long as the eyewitnesses agreed that you acted with valid provocation and fought according to their idea of 'fair play', which included things like not stabbing and attacking with the flat of the blade unless the other guy escalated the fight (or unless the provocation was sufficiently severe).

Anyway, these two images are from that article, pardon the poor quality due to my phone having a rather crap camera and I don't have the cable for it here at home so I had to go through a pretty convoluted process to get the images uploaded.

This first image shows some statistics related to our discussion. The author looked at about 700 remission letters and sorted some of the details. Where were people wounded (each letter involved a case that could involve between 1 and several peoples suffering injuries), and whether the wound was fatal.

You can see that the worst place to be hit was the lower torso and the side, followed by the neck and the upper body. The limbs were obviously the 'safest' place to be wounded, but wounds to the thighs and buttocks were fatal 58% of the time, lower legs 44%, and even in the hands and arms, the wounds were fatal 27% of the time. These latter were mostly cuts. This is spite of the fact that they had pretty good treatments for cuts, (much less so for thrusts).

The author of this article also states that 'instant death' was rare and usually correlated with injuries to the neck and the head. The majority of fatal cases died after a few days. It's also interesting that the places most often hit were the upper and middle body and the head.

This next table isn't directly related to our argument, but I thought people here might find it interesting. It shows, in the relatively small number (75)cases the author could find where both individuals were armed and with different weapons, which weapon was used by the 'winner' and which by the 'loser' (the person who ended up wounded and / or killed).

Some of the stats were unfortunately cropped out by my photo, but he shows that the most effective weapon in this sample (again, a small number of cases) was the halberd (70%), followed by the spear (55%), which in turn is followed closely by the dagger (53%) and the sword (48%). The mace and the dussack (a term he used for all saber like weapons) did relatively poorly at 39% and 31% respectively.

The halberd, the spear and (especially) the dagger are all weapons which don't get a lot of love in most RPG systems; I for one have always felt that the dagger, an actual dagger especially as in a 10 or 12 inch double-edged knife (let alone the much larger weapons which also fall into this category), is a really dangerous, lethal weapon! I never got why RPG's portray them as sort of nuisance weapons. A dagger is at a disadvantage to hit initially at the onset of a fight in any open area, but once you get close, the tables turn and the dagger has the advantage, bigtime. In terms of dangerous results, my personal opinion is that assuming a blade strong enough not to break, and with a length of over 8", a dagger (bayonet etc.) is just about as lethal as a sword in terms of the consequences of the wound.

One of the other interesting comments he made in the article is that people used the Halberd at close range by choking up and sort of punching with the business end, which is something I never heard of before.

G

-

2013-06-30, 09:27 AM (ISO 8601)Orc in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Location

- Marburg, Germany

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Yup, that's pretty much what I was going to say about it, too. His explanation is definitely great, he did lots of good research, and he deserves credit for being the first to point it out - but the findings are actually far less revolutionary than they're made out to be.

Saying that medieval craftsmen used constructions with compass and straightedge and mystical numerical properties in their design is like saying modern engineers use rulers, rational numbers and the sacred properties of the artifacts that define the metric system stored somewhere in Paris. It's technically true, but completely misses the point.

People use the simplest and most reliable tools for design they have available at the time. And if they do something that requires expensive materials and a lot of work, they'll do a design first and not rush head first into construction.

If I were to make a sword and had to get balance, harmonics etc right, I'd either take one that works, or carve a wooden mockup, and adjust that until I'm happy with its handling. Then I'd measure that thing, and use these measurements as a basis for forging a new one. Otherwise, I might waste lots of materials and work on a faulty design.

If I don't have a ruler to measure it, I'd have to find an (approximate) construction with compass and straightedge to get it right. Any actual sword built from this design will of course have the exact proportions, even if my "perfect" mockup didn't. And as Peter pointed out, using a construction instead of measurements means that I can easily scale my design up or down without using a pocket calculator or risking to get the numbers wrong.

TL;DR: There needn't be a mystical reason for this design approach. It's simply the smart thing to do with the tools they had at the time.Want a generic roleplaying system but find GURPS too complicated? Try GMS.

-

2013-06-30, 11:05 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Yes but the fact is, they did put all these mystical meanings onto the numbers, as part of their interest in astrology and numerology and so forth. It was part of the education most people got back then. It doesn't mean it wasn't also prosaic, but they tended to group things together by what they saw as their innate characteristics of certain numbers.

So they tended to see 3 as associated with the trinity and 1 with the sun and 5 with the rose (and therefore noble or lucky) and 8 with Saturn and therefore bad luck and so forth.

This was strongly linked to both weapon design and fencing, as we know the fencing master Talhoffer included one of the earliest European astrological discursions in his 1459 fencing manual, nor was he by any means the last.

Sol was associated with fencers while mars was associated with robbers, killers and warfare. War was looked upon as evil but martial skill as a good. You can see the concepts displayed clearly in these plates from the Schloss Wolfegg Hausbuch

Sol (note the fencers in the top of the plate)

Mars (note the death and mayhem of a village raid)

How literally they believed all that stuff is an entirely different question. I suspect from what I have read, in most cases - not very. Their sources for these ideas were from ancient Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian (and so forth) sources, whose theology they didn't necessary adhere to. But they saw the patterns did exist and were useful. I think part of understanding the medieval mind is that they tended to carry around a lot of 'provisional' ideas in their heads.

But while they may not have believed literally that the astrological nature of the salt of saint peter, brimstone, and charcoal combined in such a way as to make fire, they did know that following the pattern gave them gunpowder. And gunpowder go bang.

Similarly, they knew certain mystical patterns, which they could assign to Sol or Venus or Luna or whomever, allowed them to put together very nice swords. As HP Lovecraft said, you don't have to believe in Santa Claus to get Christmas presents on Dec 25.

G

-

2013-06-30, 11:59 AM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2007

- Location

- Cippa's River Meadow

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I know you can do it with a spear, holding it with the head on the thumb side of the grip, turning it into essentially a big dagger. I would presume it would be the same way with a halberd.

As an aside, looking up some western halberd techniques videos, I'm quite surprised in that in some places, they're almost aikido-esque in joint and body manipulation: ARMA halberd techniques.Last edited by Brother Oni; 2013-06-30 at 12:08 PM.

-

2013-06-30, 02:46 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Yeah it's very similar to Aikido or Jujitsu, especially the Giocco Stretto / 'ringen' (grappling, with and without weapons) stuff

G

-

2013-06-30, 08:55 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

While they did assign various mystical qualities to particular numbers, it's not clear that they used it to influence sword design. The problem is just about every number has an association-- so whether or not that association was something the designer had in mind when the sword was designed, or something observed and assigned *after* the sword was designed is essentially unknowable.

Returning to the video: during the question and answer period, someone asks a question about scaling a sword to the customers size. During his response Johnsson first shows how the sword can be scaled geometrically, then he points out that if the customer doesn't like the ratio of hilt to blade, the designer can easily change the number of "circles" use to make it. That process would totally wreck any *predetermined* numerology going on with the sword design. Johnsson himself seems to imply that any mystical qualities associated with numbers and ratios would take a back seat to practical results.

-

2013-06-30, 09:07 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

One other thing I should mention, but it's kind of complicated, and I'm having trouble articulating it --

Briefly, Medieval, and even Renaissance thinkers, often talked about designing things from first principles, using numerology in their designs, etc., then seemed to generally ignore that in their actual constructions. This wasn't seen as a contradiction to them. Kepler, who determined that the planets travelled in elliptical orbits around the sun, also had a crazy theory about the planets involving nested shells and platonic solids. He never gave up on that theory.

-

2013-06-30, 11:30 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

G -- I agree what you're saying, but just to correct something, they didn't study Euclid in his original words; the translations (usually in Latin) were often flawed (I know with Euclid some poorly translated postulates caused some problems). ;-)

Also, they sometimes believed that all ancients were in agreement with each other and would come up with weird hybrid theories to attempt to explain away contradictions.

-

2013-06-30, 11:33 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

That is what I was trying to get at upthread. I believe this kind of "provisional" thinking is the main thing that differentiates medieval, early-modern, and even pre-Christian / pagan European people from today. We live in a Cartesian world where people are taught to expect that everything has a precise value or quantity, every theory is either wrong or right, every question has a definitive answer. I think people back then were much more comfortable with contradictions, with the idea that theories were limited but still useful.

I mean, they had to be. They studied alchemy from Muslim sources, astronomy from pagan Greek (usually via Muslim) sources, rhetoric (from whence that Cartesian thinking eventually sprang) via Greek and Roman sources, and a lot of their numerology from Hebrew sources, Philosophy from a mixture of ancient pagan Greeks, Roman Christians and medieval scholars, and so on. For example, to learn medicine they studied Galen (a Romanized 3rd Century Greek who believed in the Latin gods), Hippocrates (a 5th Century BC pagan Greek), and Avicenna (an 11th Century Muslim Persian). A nominally Christian man studying medicine in 14th Century Bologna or Krakow couldn't believe all these authors literally, these auctores, the authorities, who he or she was studying, and yet they (especially the so-called Scholastics) were trained to consider them all the experts from whom all the answers were derived. It's a built-in contradiction.

Those who studied Euclid were studying him in his original words. Epicurus, wildly popular in the middle ages originally included manners for holding orgies (a lot of this kind of stuff was edited out of the editions most commonly available today by the Jesuits in later centuries). They were passing around these ancient books like prizes. All the books were full of religious heresies, magic, superstition, the politics and ideology of another people in another age, and all their crazy ideas. But mixed in all that were threads of genius, and the genius of the medieval people was that they were able to figure all that out and double-down on it. If you have ever seen the artwork of the Renaissance Masters up close and personal, or if you ever had a chance to walk the streets of Venice, or Prague, or Strasbourg, or (and I know this is a bit more of a stretch but) if you've ever handled an authentic medieval sword, I think you know exactly what I mean.

G

-

2013-06-30, 11:39 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Yeah what I mean is, flawed translations or not, they read directly what he wrote, or tried to if they could, rather than summaries, interpretations or the 'cliff notes' version people often get today.

I think a lot of the convoluted theories which tried to synthesize what the ancients said into proper Christian orthodoxy of their time, was a sort of game played in the Universities, particularly the theological schools like Paris and Cologne, and despite the brilliant efforts by some of those theologians to fit that square peg into that round hole (Thomas Aquinas perhaps first among others), who contributed to certain academic trends (i.e. the Scholastics), they were obviously papering over a rather big hole. In the end it was the Franciscans (Roger Bacon, William of Ockham) and the Humanists who sort of won that debate in the long term, most of whom were much more enamored of the original sources than any more modern theological interpretations (in fact some of them openly advocated a return to the pagan religion of the ancient Greeks)

G

-

2013-07-01, 07:04 AM (ISO 8601)Orc in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Location

- Marburg, Germany

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

I can't really agree with this. Scientists and engineers still know that their models are, strictly speaking, "wrong". They are just getting more and more accurate with each new discovery, and in most cases they don't even use the most accurate model when an inaccurate one is good enough. If you want to build a bridge, you'll go with Newton mechanics, even though special relativity is the "more accurate" way to handle it. If you want to launch satellites, Newton isn't good enough, so you go all the way.

What scientists don't accept are straight contradictions, and rightfully so. If you use inaccurate models, you should know how inaccurate they are - and assigning a margin of error removes the contradiction between different models (if done right), but still lets the models make useful and verifiable predictions.

The question whether a definitive answer even exists is best left to philosophers. The Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics is a prime example of deciding not to answer this question - Feynman famously summarized it as "shut up and calculate!".Want a generic roleplaying system but find GURPS too complicated? Try GMS.

-

2013-07-01, 11:11 AM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Apr 2009

- Location

- Germany

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

How far a distance can a rider with a single horse cover in 8 hours, if he is not particularly exhausting the horse and keeps it at a pace they can maintain for several days. Assuming feeding and water is easily available along the way.

We are not standing on the shoulders of giants, but on very tall tower of other dwarves.

Spriggan's Den Heroic Fantasy Roleplaying

-

2013-07-01, 12:08 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2007

- Location

- Cippa's River Meadow

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Is that 8 hours in a single go, or 8 hours spread over the day?

With frequent rests and good terrain, a horse can travel for 8 hours spread over the whole day, averaging between 3-8 mph (walking to trotting). 25-30 miles a day is usually regarded as a good day's distance.

With frequent horse changes and a hard pace, you can cover up to 100 miles a day - the Mongols were renown for this level of mobility and the modern day Tevis Cup keeps up the tradition of endurance riding.

If you meant 8 hour stretches with no resting then the horse is likely to tire quickly after the first couple days and you'd cover significantly less distance.

-

2013-07-01, 12:26 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Apr 2009

- Location

- Germany

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

The 40 miles per day in D&D looked a bit fishy to me. But those were calculated based on the assumption that a horse has a walking speed more than twice of a human, which isn't actually the case.

But what's the deal with the endurance of horses? You can catch horses on foot by simply following them until they are too exhausted to continue fleeing, as humans can keep walking for much longer durations.

So does riding a horse actually make you faster on long distances, or is it just less tiresome for the rider than walking himself?We are not standing on the shoulders of giants, but on very tall tower of other dwarves.

Spriggan's Den Heroic Fantasy Roleplaying

-

2013-07-01, 01:27 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2007

- Location

- Cippa's River Meadow

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Less tiresome, but if you set the pace hard, you can travel a greater distance for the same amount of time.

The Mongols used several horses, changing out regularly to keep them all relatively fresh, so they could keep the same high pace throughout.

I know many cultures and/or organisations use relay stations with fresh horses so that riders or messengers can change their mounts then hurry on to the next waystation.

The Pony Express had waystations set up every 10 miles as that was about as far as a horse could gallop (~30mph) before it tired.

The Romans had a similar system and there's apparently a map of their road system along with their messenger changeover points, or stationes.

I'm not familiar with horse anatomy and their biology, so will need to do some research.

Edit: D'oh, I'm an idiot. The primary reason is apparently thermoregulation - horses have less surface area to volume ratio than humans and additionally generate greater heat when exerting themselves: link.Last edited by Brother Oni; 2013-07-01 at 01:36 PM.

-

2013-07-01, 01:36 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Dec 2008

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

The big advantages to horses are that it's a lot easier on the rider, and that you can carry more stuff. I mean, if you give me the choice between walking 20 miles carrying 50 pounds of gear and riding that distance, I'll take the horse. If that's harder on the horse than it would be on me, I can live with that. And since I rarely walk 20 miles at a time, the horse is probably better at it than I am anyway.

-

2013-07-01, 02:30 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Re: Got a Real World Weapons or Armour Question? Mk XII

Depends on the weather conditions, road and / or terrain conditions, and the gait. A horse which can do the ambling gait (rare today) could sustain a pretty fast pace for a really long time.

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2013-07-01 at 02:31 PM.

RSS Feeds:

RSS Feeds: